Marina Chen still remembers the exact moment she first saw the underwater high speed train proposal. She was waiting for the delayed 6:47 AM ferry to Hong Kong, scrolling through news on her phone, when the computer-generated images stopped her cold. Sleek silver trains gliding through glass tunnels beneath crystal-blue waters. Passengers sipping coffee while fish swam overhead.

“I thought it was a movie poster,” she laughs, adjusting her laptop bag. “Then I realized they were serious about actually building this thing.”

Marina isn’t alone in her disbelief. Millions of people across Asia and Africa are wrestling with the same question: could the world’s most ambitious transportation project actually become reality?

The audacious vision beneath the waves

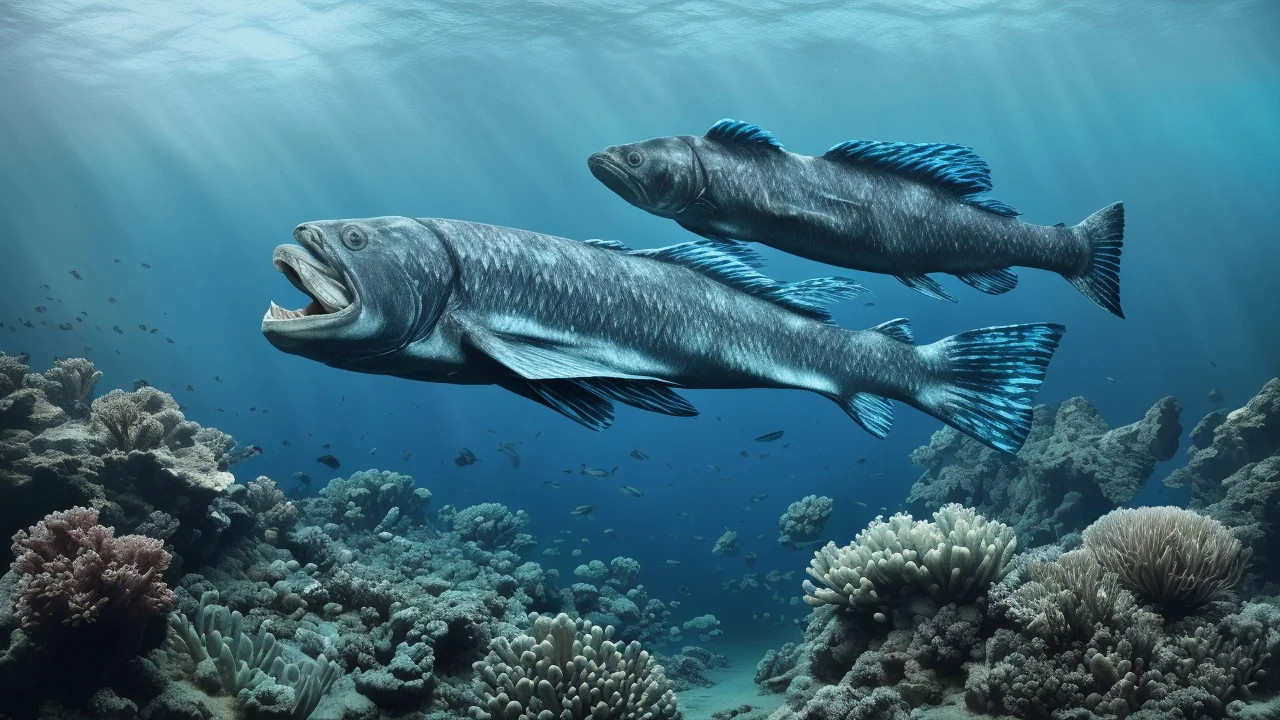

The proposed underwater high speed train would stretch thousands of kilometers, connecting major cities across multiple continents through a network that includes hundreds of kilometers of underwater tunnels. Picture boarding a train in Shanghai, then stepping off hours later in Lagos, Nigeria—all without ever seeing an airport security line.

The scale defies easy comparison. While Japan’s Seikan Tunnel runs 53 kilometers underwater and the Channel Tunnel spans 50 kilometers beneath the English Channel, this project envisions underwater sections several times longer, plunging through some of the world’s deepest ocean trenches.

“We’re not talking about connecting two nearby islands,” explains Dr. James Liu, a transportation infrastructure specialist. “This would be like building multiple Channel Tunnels back-to-back, except through much deeper and more challenging waters.”

China’s existing high-speed rail network provides the foundation for such ambitions. With over 40,000 kilometers of high-speed track already operational and trains regularly hitting 350 km/h, the country has proven it can move massive numbers of people quickly over land. The underwater component represents the next logical—if monumentally challenging—step.

Breaking down the impossible numbers

The engineering specifications read like something from a science fiction novel, but they’re rooted in real calculations and existing technology pushed to its absolute limits.

| Component | Specification | Challenge Level |

|---|---|---|

| Total Length | 8,000+ kilometers | Unprecedented |

| Underwater Sections | 400+ kilometers | Extreme |

| Maximum Depth | 200+ meters below seafloor | Extreme |

| Operating Speed | 300-400 km/h | High |

| Tunnel Diameter | 12-15 meters | High |

| Estimated Cost | $200+ billion | Staggering |

The construction methods would combine multiple approaches:

- Tunnel boring machines for sections through stable bedrock

- Immersed tube technology for shallower coastal areas

- Floating tunnel concepts for the deepest ocean crossings

- Artificial island stations for passenger and maintenance access

“The technology exists for every individual component,” notes Sarah Martinez, a marine engineering consultant. “The question is whether we can combine them all successfully at this scale while keeping costs from spiraling completely out of control.”

Pressurization systems would need to maintain comfortable conditions for passengers while accounting for massive external water pressure. Emergency protocols would require underwater rescue capabilities unlike anything currently deployed.

What this means for the world

If completed, an underwater high speed train network would fundamentally reshape global travel patterns and economic relationships. The implications stretch far beyond transportation.

For travelers, the math is compelling. A journey that currently requires 15+ hours of flying with connections could potentially be completed in 8-10 hours of continuous high-speed rail travel. No security delays, no weather cancellations, no jet lag from changing time zones rapidly.

Economic corridors would emerge almost overnight. Cities currently separated by oceans could develop the kinds of integrated economic relationships typically seen between land-connected regions. “Imagine if Singapore and Cairo had the same connectivity as Paris and London,” suggests transportation economist Dr. Ahmed Hassan.

The environmental implications are equally significant. High-speed rail produces roughly one-third the carbon emissions per passenger-kilometer compared to aviation. A successful underwater network could eliminate millions of flights annually.

But the challenges remain enormous:

- Geological risks: Earthquake zones, shifting seafloors, and unstable sediments

- Marine ecosystem impacts: Construction effects on ocean life and habitats

- Maintenance complexity: Repairs hundreds of meters underwater

- Security concerns: Protecting infrastructure in international waters

- Political coordination: Managing agreements across multiple countries

“The engineering is hard, but the politics might be harder,” admits Liu. “You need stable, long-term commitments from governments that traditionally don’t always see eye to eye.”

Current projections suggest the first underwater segments could begin testing by the mid-2030s, with full network completion potentially decades away. Even optimists acknowledge the timeline could stretch much longer if unexpected complications arise.

For now, Marina Chen and millions of others wait to see whether this underwater high speed train vision will join the ranks of humanity’s greatest engineering achievements—or remain forever in the realm of beautiful computer renderings.

“Part of me hopes they try,” she says, watching another ferry navigate the choppy waters. “Even if they fail, we’ll learn something incredible in the process.”

FAQs

How deep would the underwater high speed train tunnel go?

The tunnel would likely run 100-200 meters below the seafloor, with total depths reaching 300+ meters below sea level in some sections.

How long would it take to travel from Asia to Africa?

Initial estimates suggest 8-12 hours for the complete journey, depending on the specific route and number of stops.

What happens if there’s an emergency underwater?

Emergency protocols would include pressurized escape pods, underwater rescue vessels, and emergency stations at regular intervals along the route.

How much would tickets cost?

While no official pricing exists, experts estimate costs similar to or slightly higher than current long-haul flights between the same destinations.

When could construction actually begin?

Preliminary surveys and planning could start within the next 5-10 years, but major construction likely wouldn’t begin before the 2030s.

Has anything like this been built before?

The Channel Tunnel and Japan’s Seikan Tunnel provide precedents, but this project would be several times longer and much deeper than existing underwater rail tunnels.