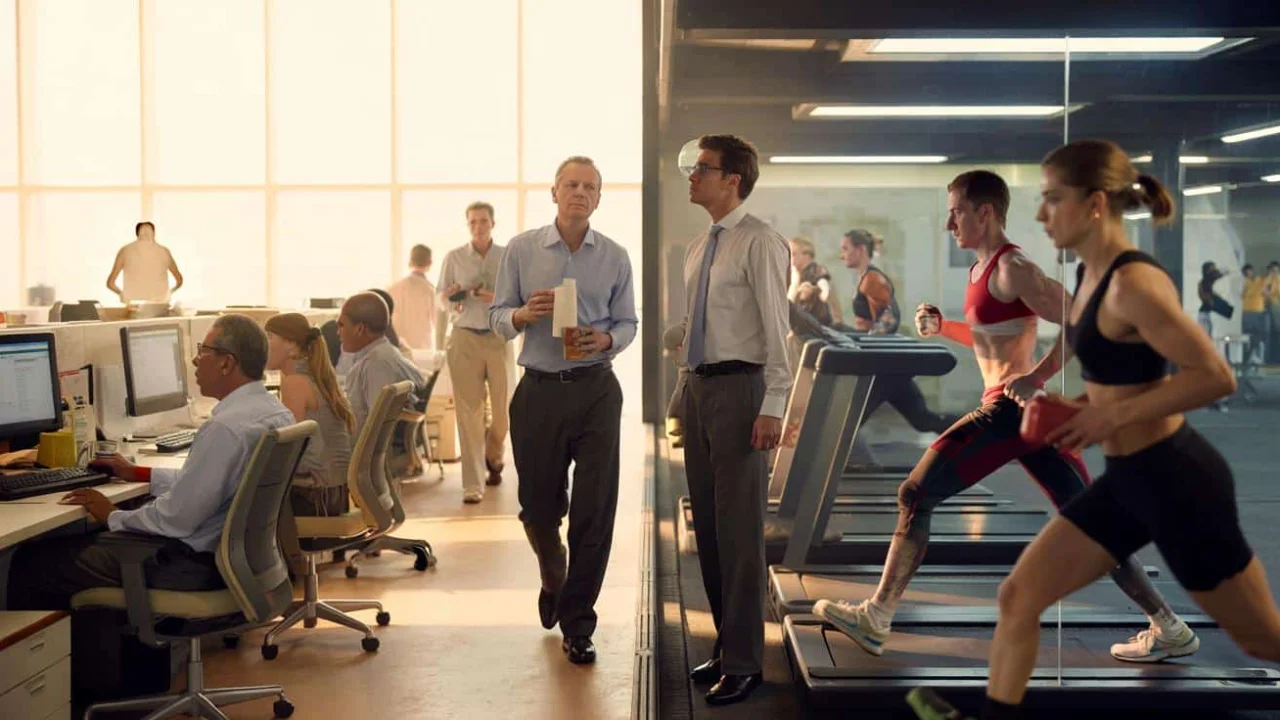

Maria stared at her closet, holding a pair of barely-worn sneakers she’d bought during a New Year’s resolution that lasted exactly three weeks. Like millions of people, she’d decided to donate them rather than let them collect dust. She drove to her local Red Cross drop-off point, feeling good about giving her shoes a second life with someone who needed them.

What Maria didn’t know was that across the country, another donor had the same idea—except he decided to find out exactly where his donation would end up. He slipped a small Apple AirTag into his sneakers before dropping them off, turning what should have been a simple act of charity into a viral investigation that forced one of the world’s largest humanitarian organizations to explain itself.

The story that unfolded would challenge everything people thought they knew about what happens to their donated items.

When Good Intentions Meet Reality

The donor’s experiment started innocently enough. He placed an AirTag—the same device people use to track lost luggage—inside his donated sneakers and watched as they began their journey through the Red Cross donations system. What he discovered on his phone’s tracking app told a very different story than the one most donors imagine.

Instead of going directly to someone in need, the sneakers traveled first to a sorting facility, then to a warehouse, and finally to an industrial area known for wholesale operations. When he shared screenshots of the tracking data online, the post exploded across social media platforms.

“I thought I was helping a homeless person get shoes,” wrote one commenter. “Turns out I was feeding a business model I never knew existed.”

The tracking revealed that Red Cross donations don’t always follow the straightforward path most people envision. While some items do reach people in crisis directly, others enter a complex logistics network that includes resale, recycling, and export operations.

Dr. Sarah Williams, who studies nonprofit operations, explains the reality: “Most people donate with a very specific image in mind—their sweater warming someone on a cold night. But large-scale humanitarian work requires sustainable funding models that go beyond individual feel-good moments.”

Where Your Donations Actually Go

The Red Cross’s response to the viral tracking incident shed light on the various paths donated items can take. Here’s what actually happens to most Red Cross donations:

- Direct distribution: Clean, appropriate items go immediately to disaster victims and people in emergency situations

- Charity retail: Items sold in Red Cross thrift stores, with proceeds funding humanitarian programs

- Bulk sales: Surplus donations sold to textile recyclers or overseas buyers to generate operational funds

- Recycling: Damaged or unusable items processed for raw materials

The organization provided detailed data about their donation processing to address public concerns:

| Donation Path | Percentage of Items | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Aid | 25-30% | Immediate crisis response |

| Retail Stores | 35-40% | Affordable community access + funding |

| Bulk Sales | 20-25% | Operational cost recovery |

| Recycling | 10-15% | Environmental responsibility |

“The reality is that processing donations costs money,” says nonprofit consultant James Rodriguez. “Sorting, cleaning, storing, and distributing thousands of items requires staff, facilities, and transportation. Selling some donations helps fund these operations.”

The Hidden Economics of Charity

The AirTag incident opened a larger conversation about the economics behind charitable giving. Many donors were surprised to learn that their contributions might generate revenue for the organizations they’re trying to support.

This revelation particularly stung during tough economic times, when people donating items often assume they’re going directly to others facing similar financial struggles. The tracking data suggested a more complex reality where charity work intersects with global trade networks.

The Red Cross emphasized that revenue from bulk sales and retail operations directly supports their humanitarian mission. When disasters strike, these funds help cover immediate response costs, staff salaries, and logistics operations that direct donations alone couldn’t sustain.

“People want transparency, and they deserve it,” acknowledges charity accountability expert Lisa Chen. “But they also need to understand that effective humanitarian work requires business models that can scale and respond quickly to crises.”

The organization has since updated their donation guidelines to better explain these processes. They now provide clearer information about how different types of donations are processed and used.

For donors like Maria, this transparency creates both understanding and complexity. While the warm feeling of direct giving might be diluted by knowledge of business operations, the broader impact of supporting sustainable humanitarian systems can be equally meaningful.

The sneaker tracking incident ultimately highlighted a tension in modern charity work: balancing public expectations of direct impact with the practical realities of running large-scale humanitarian operations. The Red Cross continues to process millions of donations annually, now with greater public awareness of where those items actually end up.

As one Red Cross spokesperson noted: “Our mission hasn’t changed—we’re still working to alleviate human suffering. But we’re committed to being more transparent about how we achieve that mission through both direct aid and sustainable funding strategies.”

FAQs

Do all Red Cross donations get sold instead of given to people in need?

No, about 25-30% go directly to people in crisis situations, while others support funding through retail or bulk sales.

Is it legal for charities to sell donated items?

Yes, selling donations to fund operations and programs is a standard and legal practice for most charitable organizations.

How can I ensure my donation goes directly to someone in need?

Contact local shelters or community organizations directly, or donate during specific disaster response campaigns.

Why don’t charities just give away all donated items for free?

Processing, sorting, cleaning, and distributing donations requires significant operational costs that must be funded somehow.

Should I stop donating because some items get sold?

Revenue from sold donations still supports humanitarian programs, so your contribution has impact even if indirect.

Can I track my donations like the sneaker experiment?

While possible, most organizations discourage this practice as it can interfere with their sorting and distribution processes.