Picture this: you’re sitting in a high school math class, staring at that familiar equation scribbled on the whiteboard. a² + b² = c². Your teacher mentions it’s been around for over 2,000 years, proven hundreds of different ways by brilliant minds throughout history. Most students nod along, maybe groan a little, then move on to the next problem.

But what if two teenagers decided that wasn’t enough? What if they looked at one of mathematics’ most sacred rules and said, “We think there’s still something left to discover here.”

That’s exactly what happened in New Orleans, where two high school students just turned the mathematical world upside down by doing something experts said was impossible.

When High Schoolers Challenge 2,000 Years of Mathematical Wisdom

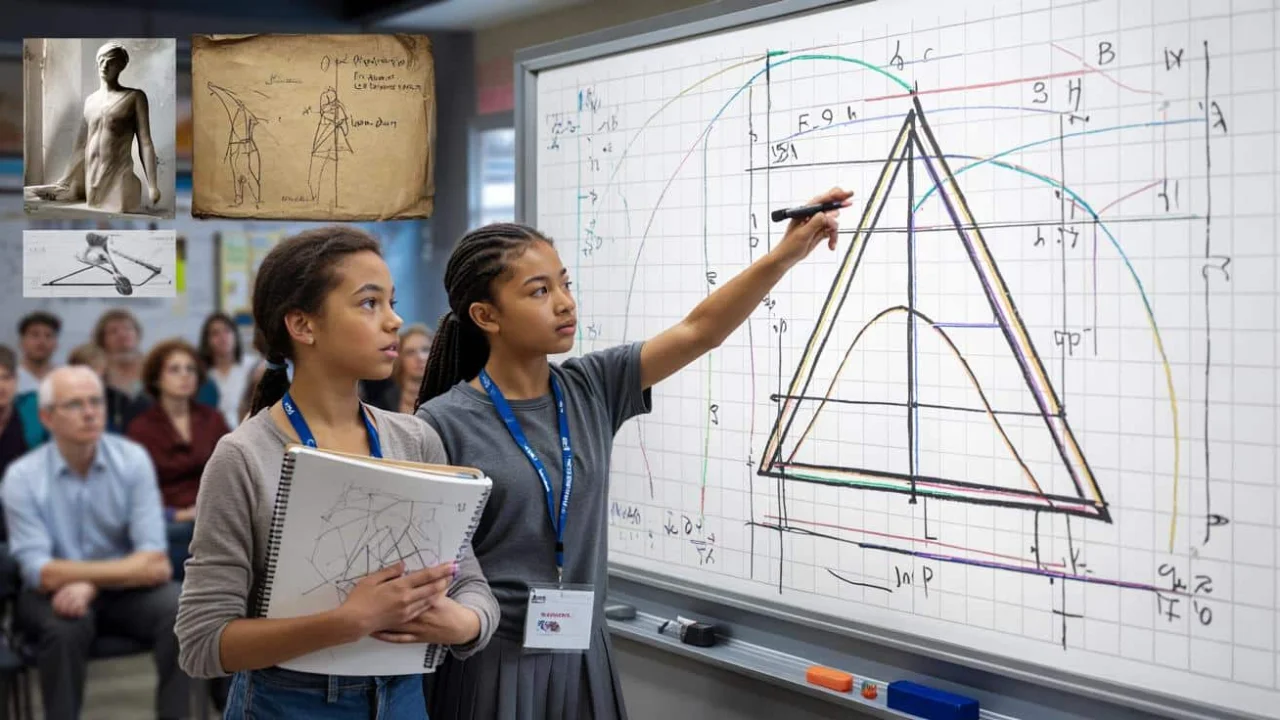

Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson weren’t trying to become famous. These two students at St. Mary’s Academy simply stumbled upon a question that had been bugging mathematicians for centuries: could you prove the Pythagoras theorem using only trigonometry?

Most experts would have laughed at the suggestion. The problem seemed impossible because of something called “circular reasoning.” Think of it like this: trigonometry traditionally relies on the Pythagoras theorem to work. So using trigonometry to prove that same theorem would be like trying to lift yourself up by your own bootstraps.

“For over 2,000 years, mathematicians believed this approach would always lead you in circles,” explains Dr. Sarah Martinez, a mathematics professor at Tulane University. “These students found a way around that fundamental roadblock.”

The teenagers spent four years working on this problem. While their classmates focused on college applications and prom planning, Jackson and Johnson were diving deep into advanced mathematical concepts that most people don’t encounter until graduate school.

Breaking Down Their Groundbreaking Discovery

So what exactly did these students accomplish? Let’s break down their achievement in terms anyone can understand.

The Pythagoras theorem states that in any right triangle, the square of the longest side equals the sum of squares of the other two sides. It’s the foundation for countless applications we use daily:

- GPS navigation systems calculating the shortest route

- Construction workers ensuring buildings are perfectly square

- Computer graphics rendering realistic 3D images

- Engineers designing everything from bridges to smartphones

Here’s what makes their discovery so remarkable:

| Traditional Approach | Jackson & Johnson’s Method |

|---|---|

| Uses geometric shapes and algebraic manipulation | Uses pure trigonometric relationships |

| Relies on over 300 existing proof methods | Creates an entirely new proof category |

| Avoids trigonometry due to circular logic concerns | Solves the circular logic problem completely |

| Established by professional mathematicians | Developed by high school students |

“What these young women accomplished is genuinely revolutionary,” notes Professor Michael Chen from MIT’s Mathematics Department. “They didn’t just find a new proof – they opened up an entirely new way of thinking about fundamental mathematical relationships.”

Their approach uses what’s called the “law of sines” in a completely novel way. Instead of falling into the circular reasoning trap, they constructed their proof using trigonometric identities that don’t depend on the Pythagoras theorem. It’s like finding a secret passage in a maze that everyone thought was sealed off.

Why This Discovery Matters Beyond the Classroom

You might be thinking, “Okay, but who cares about another way to prove an ancient theorem?” The answer is: pretty much everyone who uses technology.

Mathematical breakthroughs like this rarely stay confined to academic papers. They tend to ripple outward, influencing everything from artificial intelligence algorithms to space exploration calculations. When you discover a fundamentally new way to approach basic mathematical relationships, you’re essentially handing engineers and scientists a new tool.

“This kind of fresh thinking is exactly what we need in STEM fields,” explains Dr. Lisa Rodriguez, who leads NASA’s computational mathematics division. “These students proved that age and formal credentials don’t determine who can make breakthrough discoveries.”

The practical implications could be significant:

- More efficient algorithms for computer graphics and gaming

- Improved accuracy in navigation and mapping systems

- Better methods for teaching trigonometry to future students

- New approaches to solving complex engineering problems

But perhaps the most important impact isn’t technological – it’s inspirational. Jackson and Johnson have shown that mathematical innovation isn’t reserved for people with decades of formal training. Sometimes the most significant breakthroughs come from those willing to question what everyone else accepts as impossible.

Their work has already been published in a peer-reviewed mathematical journal, a rare achievement for undergraduate students, let alone high schoolers. Universities across the country are taking notice, and both students have received multiple scholarship offers.

“We never expected this reaction,” Johnson said in a recent interview. “We were just curious about whether something could be done differently. It turns out curiosity can take you pretty far.”

The mathematical community is now buzzing with excitement about what other “impossible” proofs might be waiting for someone brave enough to try a different approach. Jackson and Johnson have proven that even 2,000-year-old mathematical wisdom can be expanded by fresh eyes and persistent effort.

Their discovery reminds us that innovation doesn’t always come from the most obvious places. Sometimes it takes two teenagers from New Orleans, working after school hours, to shake the foundations of mathematical knowledge that scholars have accepted for millennia.

FAQs

What exactly is the Pythagoras theorem?

It’s a mathematical rule stating that in right triangles, the square of the longest side equals the sum of squares of the other two sides (a² + b² = c²).

Why was proving it with trigonometry considered impossible?

Because trigonometry traditionally relies on the Pythagoras theorem, using it to prove the theorem would create circular reasoning.

How long did the students work on this problem?

Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson spent four years developing their trigonometric proof while attending high school.

Has their work been officially recognized?

Yes, their research has been published in a peer-reviewed mathematical journal, which is extremely rare for high school students.

What makes their approach different from the 300+ existing proofs?

Their method uses pure trigonometric relationships without falling into circular reasoning, creating an entirely new category of proof.

Could this discovery have practical applications?

Potentially yes – new mathematical approaches often lead to more efficient algorithms and improved methods in technology, engineering, and computer science.