The Netherlands is a country intimately defined by its relationship with water. With a significant portion of its territory below sea level, the Dutch have developed an extraordinary set of tools and strategies for managing water, turning their geographic vulnerability into a showcase of engineering brilliance. One of the most remarkable feats in this context is the **rerouting of rivers** — a centuries-long process that has fundamentally reshaped the Dutch coastline and allowed the nation to create more habitable land through **land reclamation** and flood protection efforts.

This story is not simply one about technology or environmental management. It’s also about the Dutch people’s enduring fight against nature and their ability to adapt. Through large-scale interventions like river diversions, dyke construction, and polder creation, the Netherlands has done what many other countries consider unthinkable — it has bent the forces of nature to suit its civilian needs. From agricultural expansion to urban development and securing freshwater, rerouting rivers in the Netherlands has had a transformative effect on the country’s socioeconomic fabric.

Overview of Dutch River Rerouting Strategy

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Objective | Flood prevention and land reclamation |

| Key Rivers Affected | Rhine, Meuse, IJssel |

| Technique Used | River diversions, dike building, polder creation |

| Historical Period | Middle Ages to 21st Century |

| Major Projects | Zuiderzee Works, Delta Works, Room for the River |

| Environmental Impact | Managed ecosystems, reduced flooding, climate adaptation |

The historical roots of Dutch water management

The Netherlands’ need to control water started as early as the 12th century, when communities began building **primitive dikes** to protect themselves from devastating floods. Over centuries, political organizations known as “water boards” were formed — some of the earliest examples of democratic governance in Europe. These boards managed canals, oversaw dike construction, and coordinated the dredging of waterways.

The country’s situation at the mouth of multiple major European rivers, including the **Rhine**, **Meuse**, and **Scheldt**, placed it at particular risk from seasonal flooding and storm surges from the North Sea. In response, the Dutch didn’t just seek to hold the waters back — they sought to **re-engineer their entire landscape**. Diverting rivers became a cornerstone of their strategy, allowing them to dry out marshlands, prevent inland flooding, and make new land available for farming and development.

How rivers were rerouted over time

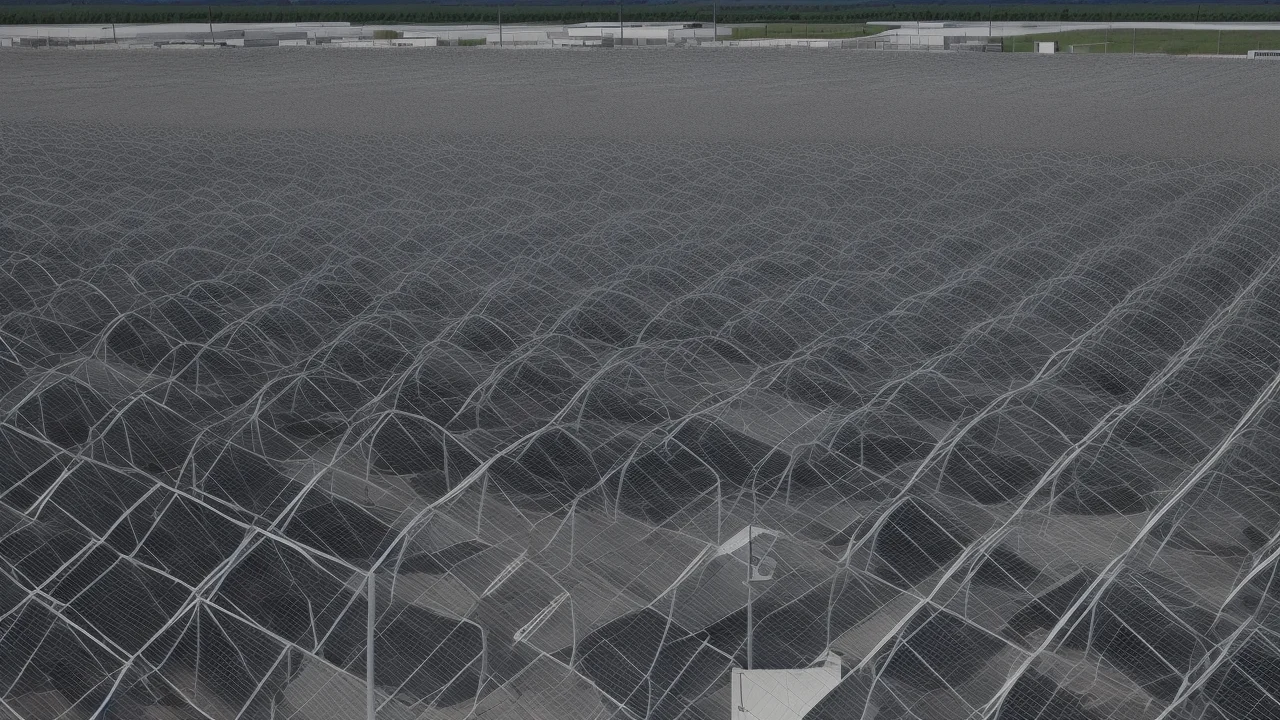

Initially, Dutch engineers made small adjustments by straightening out rivers or digging **canals** to bypass flood-prone areas. But as their knowledge and tools improved, so did the scale of their ambitions. In multiple phases, particularly between the 16th and 20th centuries, various major rivers were channeled into **new courses**. These changes impacted not only hydrology but entire landscapes and ecosystems.

The **Rhine River**, for example, was divided into multiple branches, and their flows were modified to minimize flood risk to urban areas. Similarly, the **Meuse River** was embanked and contained within a more predictable path, reducing its capacity to flood surrounding lands. Alongside this river work, the Dutch also dyked off estuaries, eventually creating massive inland lakes that could be drained to form polders — reclaimed plots of land below sea level, kept dry using pumping stations.

Major infrastructure projects that enabled coastal transformation

Perhaps the most internationally recognized Dutch water management initiatives are the **Zuiderzee Works** and the **Delta Works**. The Zuiderzee Works began in the early 20th century with the goal of turning the saltwater Zuiderzee into a freshwater lake named **IJsselmeer** through the construction of the 32-kilometer-long Afsluitdijk. This project rerouted several rivers and allowed the Dutch to reclaim thousands of hectares in Flevoland, now the country’s newest province.

The **Delta Works**, initiated after the catastrophic North Sea flood of 1953, comprised a series of dams, sluices, locks, dikes, and storm surge barriers. These extraordinary engineering feats controlled the flow of the **Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta**, strategically diverting water to reduce disaster risks while maintaining ecological balance and freshwater availability.

Room for the River: A modern approach to river management

In the late 20th century and into the 21st, climate change introduced new challenges, including heavier rainfall and rising sea levels. In response, the Dutch launched the **Room for the River** initiative — a dramatic shift in philosophy. Instead of trying to confine rivers with ever-higher dikes, authorities began creating **floodplains**, altering river paths to **give water more space** during peak flows.

This meant relocating dikes, excavating side channels, and even relocating buildings and farms to allow rivers to safely flood designated areas. Although this sounds like a reversal, it’s consistent with a deep understanding that working with water, not just fighting it, is crucial in the 21st century. It represents a mature evolution of the Dutch approach to river rerouting — a balance between safety, sustainability, and spatial planning.

Social and economic impacts of land creation

Rerouting rivers and reclaiming land has had profound effects on the Dutch economy and society. Land that once lay beneath water is now home to **vibrant cities**, **industrial parks**, and **agriculture zones** that feed both domestic and global populations. Flevoland, for instance, is a testament to the success of land reclamation and is now one of the most productive agricultural regions in the country.

However, creating land through manipulating natural watercourses comes with costs. Indigenous aquatic ecosystems are often threatened, and long-term maintenance of polders is expensive. Land subsidence also poses new risks. Still, these investments have generally paid off, securing the Netherlands’ position as a leader in **water management and urban resilience**.

Winners and those who faced challenges

| Winners | Challenges Faced |

|---|---|

| Urban planners and developers | Relocated farmers and residents |

| Farmers using fertile polder land | Disrupted wetlands ecosystems |

| Climate adaption policymakers | Financial costs of continuous maintenance |

Looking ahead: Adapting to climate change with historic lessons

Despite centuries of experience, climate change presents new variables. As sea levels rise and extreme weather becomes more frequent, Dutch engineers are **re-evaluating old assumptions**. Projects now incorporate climate projections extending to the year 2100 and beyond. Policymakers are looking at **adaptive infrastructure**, such as movable barriers, and even floating buildings that can handle shifting water levels.

With their eyes firmly on the future, the Dutch are setting examples for other delta regions worldwide. Their model — strategically choosing when to **redirect rivers**, when to let them flow naturally, and when to absorb floods instead of fighting them — may serve as a blueprint for low-lying countries facing similar challenges.

By changing the course of rivers, we didn’t just redraw maps — we reshaped lives, economies, and ecosystems.

— Diederik Samsom, Sustainability Expert and Advisor

Today’s water challenges are global. The Dutch experience with river rerouting is more relevant than ever.

— Maria Vos, Environmental Planner (Placeholder)

Short FAQs on River Rerouting in the Netherlands

What is river rerouting?

River rerouting involves altering the natural flow of rivers to prevent flooding, create new land, or maintain navigability. It often involves engineering works like canals, dikes, and floodplains.

Why did the Dutch reroute rivers?

The main goal was to protect inhabited land from floods, reclaim land for agriculture, and enable urban expansion. It also helped manage freshwater supplies efficiently.

Which major rivers were affected in the Netherlands?

The Rhine, Meuse, and IJssel rivers were significantly altered through engineering and redirection efforts over centuries.

How does the Room for the River project work?

It creates space for rivers to overflow safely during heavy rainfall by designating controlled floodplains, thus preventing unexpected floods in urban areas.

Is the Netherlands still rerouting rivers today?

Yes, modern projects continue to adapt river routes and flood zones in response to climate change and new environmental challenges.

What were the Zuiderzee and Delta Works?

These were monumental engineering projects designed to reclaim land and protect against floods by controlling the flow of water through barriers and sluices.

How much of the Netherlands is reclaimed land?

Approximately 17% of Dutch territory is land reclaimed from water, made possible through centuries of water management.

Could other countries follow the Dutch model?

Yes, particularly delta regions facing flooding risks. However, it requires significant financial investment and long-term planning.