Marie stares at her smartphone screen in disbelief as her son calls from his air force base. “Mom, you know that engine test I mentioned? The one I’ve been working on for months? We just nailed it.” She doesn’t fully understand what he does at the DGA facility in Saclay, something about testing fighter jet engines. But the pride in his voice tells her everything she needs to know.

What Marie doesn’t realize is that her son just witnessed something remarkable. That engine test represents capabilities that only one country in Europe can still pull off completely on its own.

France has quietly become the last European nation capable of building fighter jet engines with extreme precision from start to finish. While other countries grab headlines with flashy military announcements, French engineers are perfecting an art that’s slipping away from the rest of the continent.

How France Became Europe’s Last Engine Master

Walk through any French city and ask people what their country excels at. You’ll hear about wine, fashion, maybe nuclear power. Almost nobody will mention that France now stands alone in Europe when it comes to designing, building, and testing complete modern fighter jet engines.

This isn’t about corporate bragging rights. It’s about national capability that took decades to build and could disappear in a generation if not carefully maintained.

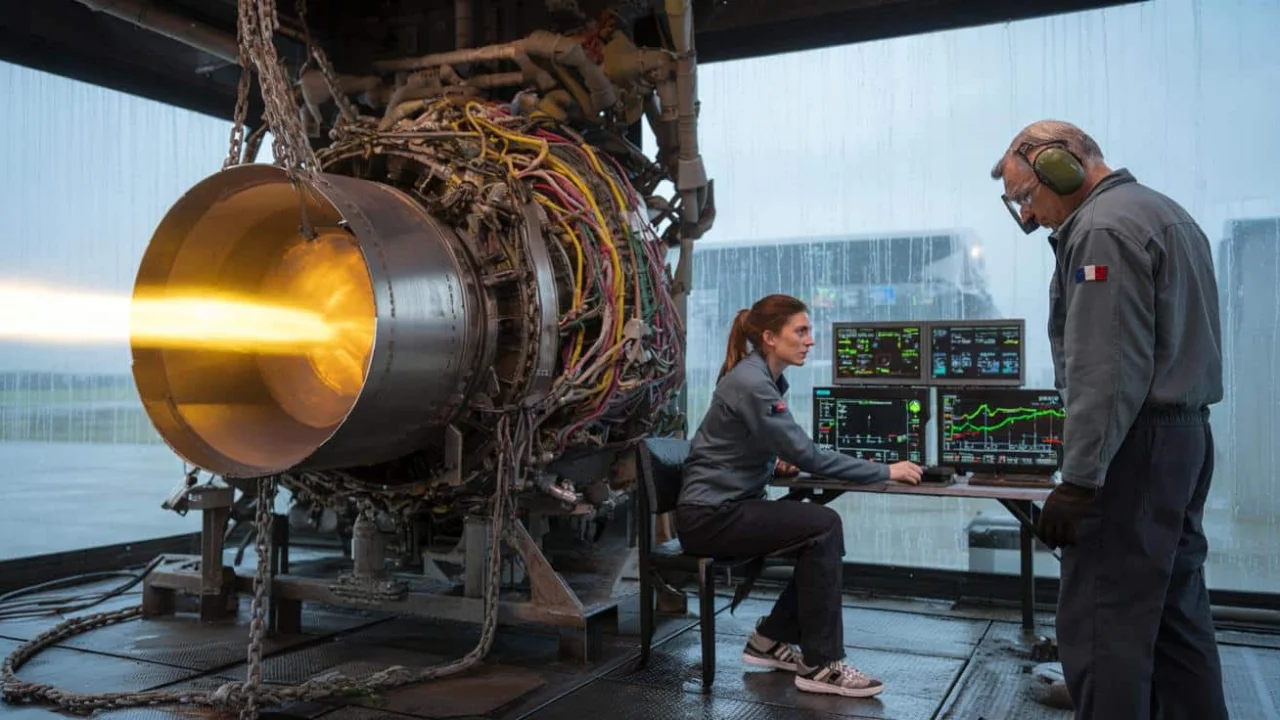

The heart of this capability beats inside the DGA – Direction générale de l’armement. Behind that bureaucratic name lies thousands of engineers and technicians scattered across France, obsessing over measurements so precise they chase individual microns and fractions of degrees.

“People think military engines are just bigger car engines,” explains a veteran DGA engineer who’s spent twenty years testing turbines. “They have no idea we’re dealing with temperatures that would melt steel and rotation speeds that would tear apart most materials.”

The M88 engine that powers France’s Rafale fighter tells this story perfectly. Born in the 1990s and continuously refined ever since, this compact powerhouse spins its high-pressure turbine at over 12,000 revolutions per minute while enduring temperatures that would destroy conventional metals.

Safran designs and manufactures the engine. Dassault integrates it into the aircraft. But the DGA serves as the unforgiving referee, testing every component and modification until it meets standards that would make Swiss watchmakers jealous.

What Makes French Engine Testing So Special

The numbers behind modern fighter jet engines reveal why this capability matters so much:

| Engine Component | Operating Conditions | Precision Required |

|---|---|---|

| High-pressure turbine | 12,000+ RPM, 1,600°C | 0.01mm tolerance |

| Compressor blades | Mach 1.5 airflow | Surface finish to 0.8μm |

| Combustion chamber | 1,850°C peak temperature | ±1°C temperature control |

| Fuel injection system | 40 bar pressure | 0.1% flow rate accuracy |

Every new engine version goes through DGA testing facilities where sensors measure the invisible – micro-deformations of turbine blades, temperature spikes lasting microseconds, the impact of a single grain of sand ingested at supersonic speed.

The testing process includes:

- Endurance runs lasting hundreds of hours under extreme conditions

- Bird strike simulations using specially designed projectiles

- Ice ingestion tests replicating high-altitude flight conditions

- Sand and dust exposure matching desert deployment scenarios

- Vibration analysis detecting potential failure modes

“We don’t just test engines,” says a DGA test facility manager. “We torture them in ways they’ll never experience in real service, then analyze every piece of data to understand exactly how and why they might fail.”

Other European countries still participate in engine development through joint programs and specialized components. Germany contributes advanced materials, the UK provides sophisticated control systems, Italy offers manufacturing expertise. But no other European nation maintains the complete capability to design, build, qualify, and support a sovereign fighter engine from concept to retirement.

Why This Matters for Europe’s Defense Future

This French monopoly on European fighter jet engines creates both opportunities and vulnerabilities that extend far beyond military circles.

For defense contractors across Europe, it means critical dependencies on French technology and testing capabilities. Countries operating French-made fighters like Egypt, India, and Qatar rely on this expertise for engine maintenance and upgrades.

The broader implications affect European strategic autonomy. As geopolitical tensions increase and supply chains face disruption, having independent engine development capability becomes a national security asset.

“Twenty years ago, multiple European countries could develop fighter engines independently,” notes a defense industry analyst. “Today, if France lost this capability, Europe would depend entirely on American or Chinese engine technology for future fighter programs.”

The economic impact extends beyond defense spending. Engine development drives innovation in materials science, precision manufacturing, and digital simulation technologies that benefit civilian industries from automotive to aerospace.

French universities and research institutes collaborate closely with DGA programs, training the next generation of engineers in skills that other European institutions no longer teach comprehensively.

For European taxpayers, this situation raises important questions about defense cooperation and industrial policy. Should other nations invest in rebuilding independent engine capabilities, or focus resources on joint European programs that leverage French expertise?

The answer may determine whether Europe maintains technological sovereignty in military aviation or gradually cedes this critical capability to global superpowers who view defense technology as a tool of diplomatic influence.

As Marie’s son continues his work testing engines that few Europeans fully understand, he’s participating in something much larger than military hardware development. He’s helping preserve capabilities that took generations to build and could reshape European defense independence for decades to come.

FAQs

What exactly does the DGA do with fighter jet engines?

The DGA tests, certifies, and monitors fighter jet engines throughout their service life, ensuring they meet extreme performance and safety standards under combat conditions.

Why can’t other European countries build complete fighter engines anymore?

Building modern fighter jet engines requires massive investment, specialized facilities, and decades of accumulated expertise that most countries have allowed to decline or fragment across joint programs.

How long does it take to test a new fighter engine?

Complete engine qualification typically takes 3-5 years of intensive testing, including hundreds of hours of operation under extreme conditions that simulate decades of service life.

Are French fighter engines better than American ones?

French and American engines excel in different areas – French engines like the M88 prioritize efficiency and maintainability, while American engines often emphasize raw power and stealth characteristics.

What happens if France loses this engine development capability?

Europe would become entirely dependent on non-European suppliers for future fighter aircraft, potentially compromising strategic autonomy and creating vulnerability to supply chain disruption.

Do civilian aircraft benefit from military engine technology?

Yes, many innovations in materials, fuel efficiency, and precision manufacturing developed for military engines eventually improve civilian aircraft performance and reliability.