Sarah noticed it first during her morning coffee routine. Her hand would freeze halfway to her mouth, the cup trembling slightly as her brain seemed to lose track of the simple movement. What should have been automatic—lift, sip, lower—now required conscious effort and perfect timing.

For millions of people with Parkinson’s disease like Sarah, the brain’s internal clock runs differently. Simple movements that once flowed seamlessly now feel disconnected, as if someone keeps adjusting the tempo of an invisible metronome controlling their every gesture.

But groundbreaking new research is revealing exactly how our brains keep perfect time, and why understanding these brain timing mechanisms could change everything for people struggling with movement disorders.

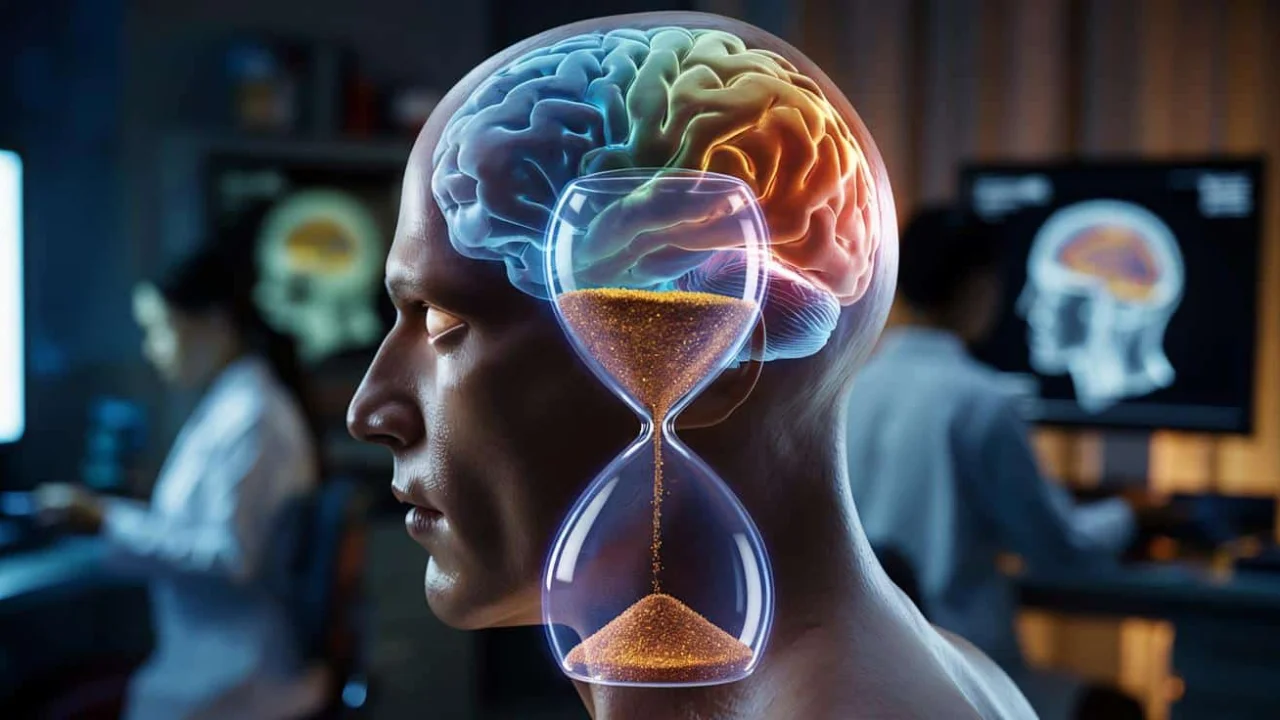

Your Brain’s Hidden Timekeeper Works Like an Hourglass

Think about the last time you clapped along to music or caught a ball. Your brain performed an incredible feat—measuring time without any dedicated organ for sensing it. We can see, hear, and touch, but time remains invisible to our senses.

Scientists at the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience have cracked this mystery. Their research, published in Nature, reveals that two brain regions—the motor cortex and striatum—work together as a sophisticated timing system that coordinates every movement we make.

“The motor cortex behaves like the top of an hourglass, sending a steady stream of signals that pile up in the striatum until it’s time to move,” explains the research team. This discovery fundamentally changes how we understand brain timing mechanisms.

The motor cortex, located near the top of your brain, acts like sand flowing from the upper chamber of an hourglass. It sends a constant stream of neural signals downward to the striatum, a deeper brain structure that catches and accumulates these signals like sand in the lower chamber.

When enough signals accumulate in the striatum—reaching a critical threshold—it triggers your intended movement. Change the flow rate from the motor cortex, and the timing shifts accordingly. It’s elegant, precise, and happening thousands of times every day without your conscious awareness.

Why This Discovery Matters More Than You Think

This hourglass model of brain timing mechanisms explains so much about human behavior and disease. Here’s what makes this research particularly significant:

- Movement precision: Your brain can adjust timing on the fly, speeding up or slowing down actions with remarkable accuracy

- Disease understanding: Both Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease heavily affect the striatum, disrupting this timing system

- Treatment potential: Knowing how timing works opens doors for targeted therapies

- Everyday applications: From sports performance to musical training, timing affects countless activities

The striatum plays a crucial role because it’s where movement decisions get fine-tuned. When this region becomes damaged, as happens in Parkinson’s disease, the hourglass system breaks down. Signals still flow from the motor cortex, but the striatum can’t process them properly.

| Brain Region | Function in Timing | Disease Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Cortex | Sends steady timing signals | Usually remains intact |

| Striatum | Accumulates signals to trigger movement | Damaged in Parkinson’s and Huntington’s |

| Connection | Hourglass-like coordination | Disrupted timing leads to movement problems |

“This shared timing system lets the brain flexibly speed up, slow down, or restart actions with surprising precision,” note the researchers. When it works properly, we take it for granted. When it doesn’t, every movement becomes a struggle.

Real People, Real Hope for the Future

For the estimated 10 million people worldwide living with Parkinson’s disease, and hundreds of thousands more with Huntington’s disease, this research represents genuine hope. Understanding exactly how brain timing mechanisms work provides a roadmap for developing better treatments.

Current treatments for movement disorders often feel like using a sledgehammer when you need a precision tool. Medications that broadly affect brain chemistry can help, but they don’t address the specific timing problems at the heart of these conditions.

“Previous work had hinted that both regions contribute to timing, but their exact roles were murky,” the research team explains. “Now we understand how these two structures actually work together to measure time.”

This precision opens exciting possibilities. Future treatments might target the specific communication between motor cortex and striatum, potentially restoring normal timing patterns rather than just managing symptoms.

The implications extend beyond movement disorders too. Athletes working on timing-critical skills, musicians perfecting rhythm, and even people recovering from strokes could benefit from therapies that enhance or repair brain timing mechanisms.

Consider how this affects daily life: every conversation requires perfect timing to know when to speak and when to listen. Walking up stairs demands precise coordination between seeing the step and lifting your foot. Even simple gestures like waving goodbye rely on this invisible timekeeper working flawlessly.

“We still clap in rhythm, hit a ball, or pause just long enough before replying in a conversation,” the researchers note. “That kind of precise timing has long puzzled neuroscientists.”

Now that puzzle is starting to make sense. The hourglass model provides a framework for understanding not just normal timing, but also what goes wrong in disease and how we might fix it.

The research team’s discovery that the brain can “flexibly speed up, slow down or restart actions with surprising precision” suggests our timing system is more adaptable than previously thought. This adaptability could be key to developing rehabilitation strategies that work with the brain’s natural timing mechanisms rather than against them.

As we learn more about how these brain timing mechanisms operate, we’re moving closer to treatments that could help people like Sarah regain the effortless movement timing that most of us take for granted. The hourglass keeps turning, and with each grain of sand—or neural signal—we’re understanding more about one of the brain’s most fundamental functions.

FAQs

How does the brain keep time without a dedicated time organ?

The brain uses two regions working like an hourglass—the motor cortex sends steady signals that accumulate in the striatum until reaching a threshold that triggers movement.

Why are people with Parkinson’s disease affected by timing problems?

Parkinson’s damages the striatum, which is the “bottom half” of the brain’s timing hourglass, disrupting the normal accumulation and processing of timing signals.

Can brain timing mechanisms be improved or trained?

While research is ongoing, understanding how the hourglass system works opens possibilities for targeted therapies and rehabilitation strategies that work with natural timing processes.

What everyday activities depend on brain timing mechanisms?

Nearly everything—walking, talking, catching objects, playing music, and even knowing when to pause in conversation all rely on precise brain timing.

How might this research lead to new treatments?

By understanding exactly how motor cortex and striatum coordinate timing, scientists can develop therapies that specifically target the communication between these regions rather than broadly affecting brain chemistry.

Do healthy people ever experience timing problems?

Yes, fatigue, stress, alcohol, and certain medications can temporarily disrupt brain timing mechanisms, affecting coordination and reaction times.