Sarah Chen remembers the moment she realized her grandmother’s antique jewelry box was older than she thought. Not just decades old—centuries old. She held it differently after that discovery, with a kind of reverence she’d never felt before. The weight of time, of all the hands that had touched it, suddenly mattered.

Now imagine that feeling, but instead of a jewelry box, you’re holding a living creature that predates your entire family tree. That’s exactly what happened to researchers in 2006, except they didn’t know it until it was too late.

They had just killed the oldest known animal on Earth—a 507-year-old clam that had been quietly living on the ocean floor since 1499, before Columbus even dreamed of the New World.

When Science Accidentally Ended Five Centuries of Life

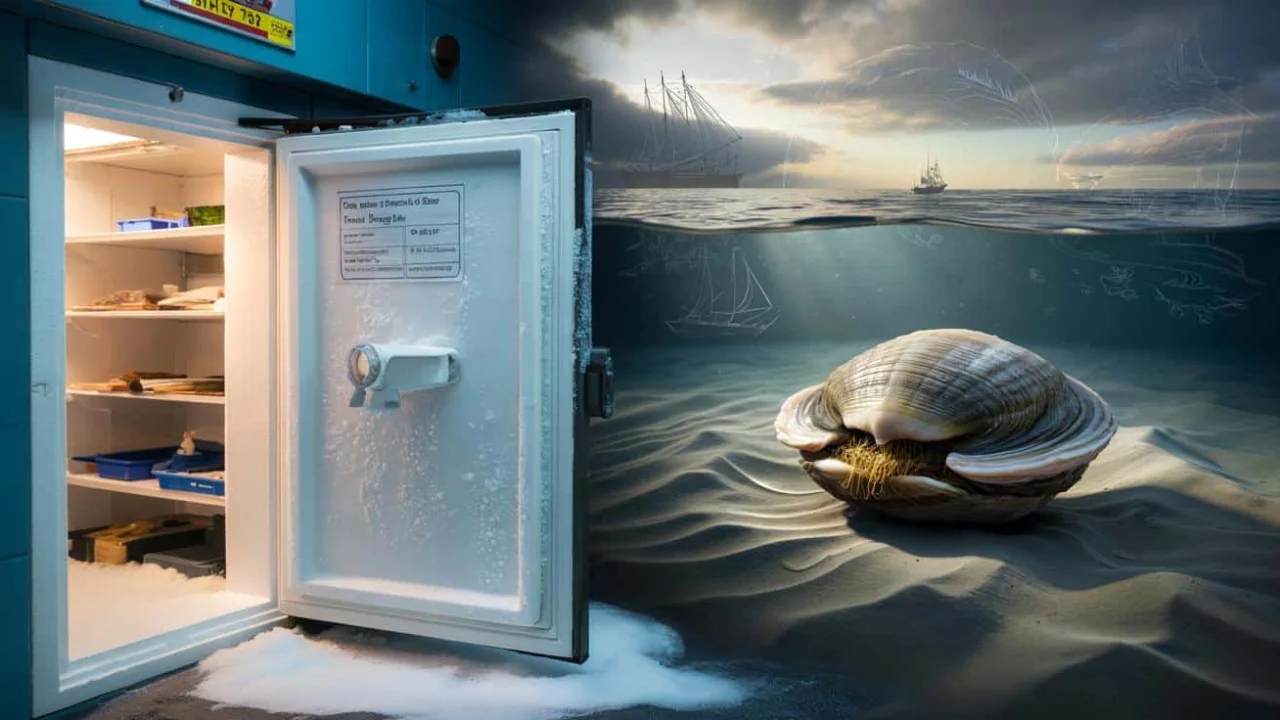

The research vessel pulled up from the frigid waters off Iceland with a routine catch. Hundreds of clams, nothing unusual. The team was studying climate patterns, looking for historical data locked inside these ancient shells. Standard procedure: collect, freeze, analyze.

One particular quahog clam, about the size of a human hand, went straight into the lab freezer at Bangor University in Wales. Just another specimen in just another research project.

But when scientists began counting the growth rings on its shell—like counting tree rings—they realized they’d made a devastating mistake. This wasn’t just any clam. This was Ming, a 507-year-old clam that had survived everything history could throw at it.

“We had no idea we were looking at an animal that old,” said Dr. Paul Butler, who led the research team. “The protocols we followed were standard, but we essentially killed the most ancient creature we’d ever encountered.”

Ming had weathered the Little Ice Age, the Industrial Revolution, two World Wars, and the beginning of climate change. What it couldn’t survive was a research laboratory freezer, set to preservation mode.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Scientific Discovery

This incident forces us to confront a difficult question: how far should science go in the name of knowledge? The answer isn’t simple, and the scientific community is still grappling with it.

Here’s what makes Ming’s case particularly complex:

- The 507-year-old clam provided unprecedented climate data spanning five centuries

- Its shell chemistry revealed temperature patterns that helped scientists understand historical ocean changes

- The research contributed to climate models that could help protect future marine life

- But an irreplaceable, ancient life was lost in the process

“The irony is that this clam’s death actually helped us understand how to better protect marine ecosystems,” explains marine biologist Dr. Jennifer Walsh. “But that doesn’t make it feel any less tragic.”

| What Ming Witnessed | Year Range | Major Events |

|---|---|---|

| Early Life | 1499-1550 | Columbus voyages, Protestant Reformation begins |

| Young Adult | 1550-1650 | Shakespeare’s lifetime, Little Ice Age peak |

| Middle Age | 1650-1800 | Scientific Revolution, Industrial Revolution starts |

| Later Years | 1800-2006 | Modern world emerges, climate change begins |

The data from Ming’s shell showed that North Atlantic temperatures fluctuated more dramatically in past centuries than previously thought. This information is now used in climate models worldwide.

How Labs Are Changing Their Approach

Ming’s death wasn’t in vain if it teaches us something about how we conduct research. Many marine biology labs have since updated their protocols based on this incident.

Modern research teams now use several new approaches:

- Non-lethal sampling techniques that take small shell samples while keeping the animal alive

- Advanced age estimation methods before collection

- Stricter protocols for handling potentially ancient specimens

- Ethics committees that specifically consider the age factor of collected organisms

“We’ve learned to ask different questions before we collect,” says Dr. Marcus Thompson, who now heads the ethics committee at the Marine Biology Institute. “Age matters. Time matters. Some discoveries aren’t worth the cost.”

The scientific community has also developed better ways to study ancient clams without killing them. High-resolution imaging and micro-sampling techniques can now extract climate data while allowing the animal to continue living.

But this raises another question: how many other ancient creatures are we collecting without knowing their true age? Recent studies suggest there might be clams even older than Ming still living on ocean floors around the world.

“Every time we pull up a research net, we might be holding something irreplaceable,” notes Dr. Sarah Kim, who studies ancient marine life. “The responsibility is enormous.”

What This Means for Future Research

Ming’s story has rippled through the scientific community in unexpected ways. It’s changed how researchers think about the value of individual organisms versus collective knowledge.

Universities now require students to consider the “Ming principle” in their research design: could this study be harming something irreplaceable? The 507-year-old clam has become a case study in research ethics courses worldwide.

Some argue that science must be willing to make difficult trade-offs. The climate data from Ming’s shell has contributed to research that could save countless marine species from climate change. Others believe that some lives are too precious to sacrifice, regardless of the scientific benefit.

“Ming lived through the birth of the modern world,” reflects Dr. Butler, who still keeps a photo of the clam’s shell on his desk. “In some ways, ending that life to understand our world feels like the ultimate modern tragedy.”

The debate continues, but one thing is clear: Ming’s death has made scientists more thoughtful about the true cost of discovery. That 507-year-old clam may have died in a lab freezer, but its legacy lives on in how we approach the ancient life forms that share our planet.

Today, there are likely other clams just as old, still alive on ocean floors, still quietly recording history in their shells. The question is: will we be wise enough to study them without destroying them?

FAQs

How old was Ming the clam when it died?

Ming was 507 years old, making it the oldest known non-colonial animal ever discovered.

Could scientists have studied Ming without killing it?

With today’s technology, yes, but the methods available in 2006 required the clam to be killed to accurately count its age rings.

Are there other ancient clams still alive?

Scientists believe there are likely other centuries-old clams living on ocean floors, but they’re difficult to identify without disturbing them.

What did Ming’s death teach science?

It led to new protocols for handling potentially ancient specimens and sparked important discussions about research ethics and the value of individual organisms.

How do scientists count a clam’s age?

They count growth rings on the shell, similar to counting tree rings, with each ring typically representing one year of growth.

What scientific discoveries came from Ming’s shell?

Ming’s shell provided detailed climate data spanning 507 years, helping scientists understand historical ocean temperature patterns and improve climate models.