Marine biologist Sarah Chen still remembers the moment she first saw a coelacanth photograph in her college textbook. “I thought it was fake,” she laughs now. “It looked like someone had glued fins onto a medieval knight’s armor.” That same sense of disbelief washed over three French divers when they descended into Indonesian waters last month, not expecting to make history.

But history found them anyway, 80 meters below the surface off Sulawesi’s coast. For the first time ever, researchers captured high-definition footage of a coelacanth living fossil in Indonesian waters—a discovery that’s sending shockwaves through the marine biology community.

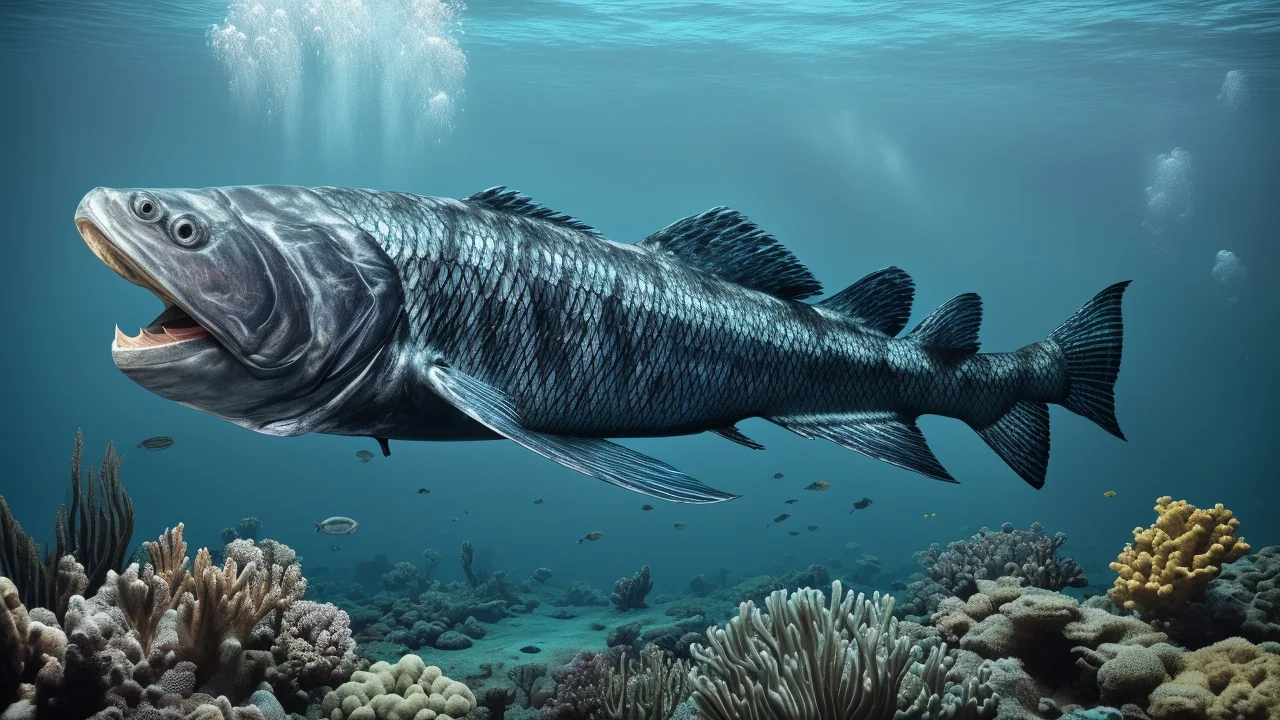

The footage shows something that shouldn’t exist: a fish that looks exactly like its ancestors from 400 million years ago, moving slowly through the deep like a living piece of ancient Earth.

Why This Ancient Fish Refuses to Change

The coelacanth living fossil represents one of evolution’s most stubborn success stories. While other species adapted, evolved, and often went extinct, this prehistoric fish found a winning formula and stuck with it.

Scientists thought coelacanths had vanished with the dinosaurs until 1938, when a fishing boat hauled one up near South Africa. Since then, researchers have found small populations near the Comoros Islands and a few scattered locations, but Indonesian waters remained mysterious.

“We’ve been looking for Indonesian coelacanths for decades,” explains Dr. James Morrison, a deep-sea specialist at the Marine Research Institute. “Finding them changes our entire understanding of where these ancient fish live and how they’ve survived.”

The French diving team from Marseille wasn’t even specifically hunting for coelacanths. They were documenting deep-water coral formations when their lights illuminated something that made them freeze mid-swim.

What makes coelacanths so special isn’t just their age—it’s how little they’ve changed. Their lobe-shaped fins contain bone structures similar to early land animals. Their scales are thick and armor-like. Even their internal organs follow an ancient blueprint that most fish abandoned millions of years ago.

Breaking Down the Discovery

The Indonesian coelacanth footage reveals several crucial details that scientists have been dying to confirm:

- Depth range: The fish was found at 80 meters, deeper than most previous Indonesian sightings

- Behavior: Unlike museum specimens, this coelacanth showed natural swimming patterns and feeding behavior

- Size: Estimated at 1.5 meters long, typical for adult coelacanths

- Habitat: Living near volcanic rock formations, suggesting specific environmental preferences

- Coloration: Distinctive blue-gray scales with white patches, matching genetic predictions for Indonesian populations

| Coelacanth Populations Worldwide | Location | Discovery Date | Estimated Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Indian Ocean | Comoros Islands | 1938 | 300-400 individuals |

| East Africa | Tanzania, Kenya | 2003 | Unknown |

| Indonesian | Sulawesi waters | 1998 (genetic), 2024 (filmed) | Unknown |

The diving team used specialized low-light cameras designed for deep-sea work. “Regular underwater cameras would have captured nothing but black water,” notes team leader Pierre Dubois. “These fish live in a world where sunlight never reaches.”

What’s remarkable is how the coelacanth moved. Instead of the rapid, darting movements of modern fish, it swam with deliberate, almost prehistoric grace. Its thick fins moved independently, more like limbs than traditional fins.

What This Means for Ocean Conservation

Finding a living coelacanth living fossil in Indonesian waters isn’t just a cool science story—it has real implications for how we protect marine environments.

First, it proves that deep Indonesian waters harbor species we’re only beginning to understand. These ecosystems face pressure from deep-sea fishing, mining interests, and climate change. Protecting coelacanth habitat means protecting entire underwater communities.

Second, it changes conservation priorities. “If coelacanths live in Indonesian waters, we need to completely reassess our protection strategies,” explains Dr. Lisa Rodriguez, a marine conservation specialist. “These aren’t just rare fish—they’re living links to our planet’s biological history.”

The discovery also highlights how much we still don’t know about ocean life. If a six-foot prehistoric fish can hide in plain sight for decades, what else is down there?

Local fishing communities in Sulawesi have reported strange “armored fish” for years, but their descriptions were often dismissed as folklore. This footage proves that traditional knowledge often contains scientific truth.

Conservation groups are now pushing for expanded marine protected areas around coelacanth habitats. Unlike surface fish, these ancient creatures can’t simply move to new areas if their environment changes. They need specific conditions that took millions of years to develop.

The French divers’ footage also reveals something troubling: the coelacanth appeared to be alone. These fish typically live in small groups, suggesting the Indonesian population might be under stress from environmental changes or human activity.

“Every coelacanth matters,” Morrison emphasizes. “With such small global populations, losing even a few individuals could impact the entire species.”

The discovery comes at a critical time for marine conservation. Ocean temperatures are rising, acidity levels are changing, and deep-sea habitats face increasing industrial pressure. Finding new coelacanth populations gives scientists hope, but also adds urgency to protection efforts.

Research teams are now planning follow-up expeditions to map coelacanth distribution in Indonesian waters. They’re using environmental DNA sampling—a technique that can detect species presence from water samples—to identify other potential habitats.

The work is dangerous and expensive. Deep-water diving requires specialized equipment and extensive safety protocols. But for marine biologists, the chance to study living fossils in their natural habitat makes every risk worthwhile.

FAQs

What makes coelacanths “living fossils”?

Coelacanths have remained virtually unchanged for 400 million years, retaining ancient features like lobe-shaped fins and primitive organ systems that other fish evolved away from long ago.

How rare are coelacanths?

Scientists estimate fewer than 1,000 coelacanths exist worldwide, making them one of the rarest large vertebrates on Earth.

Where do coelacanths normally live?

Most known populations live in deep waters around the Comoros Islands and parts of East Africa, typically at depths between 100-700 meters.

Can coelacanths survive in captivity?

No coelacanth has ever survived in captivity due to their specific deep-water pressure and temperature requirements.

Why are coelacanths important to science?

They represent a crucial link in understanding how fish evolved into land animals, as their fin structure resembles early limbs.

What threats do coelacanths face?

Climate change, deep-sea fishing, habitat destruction, and their extremely small population sizes make them vulnerable to extinction.