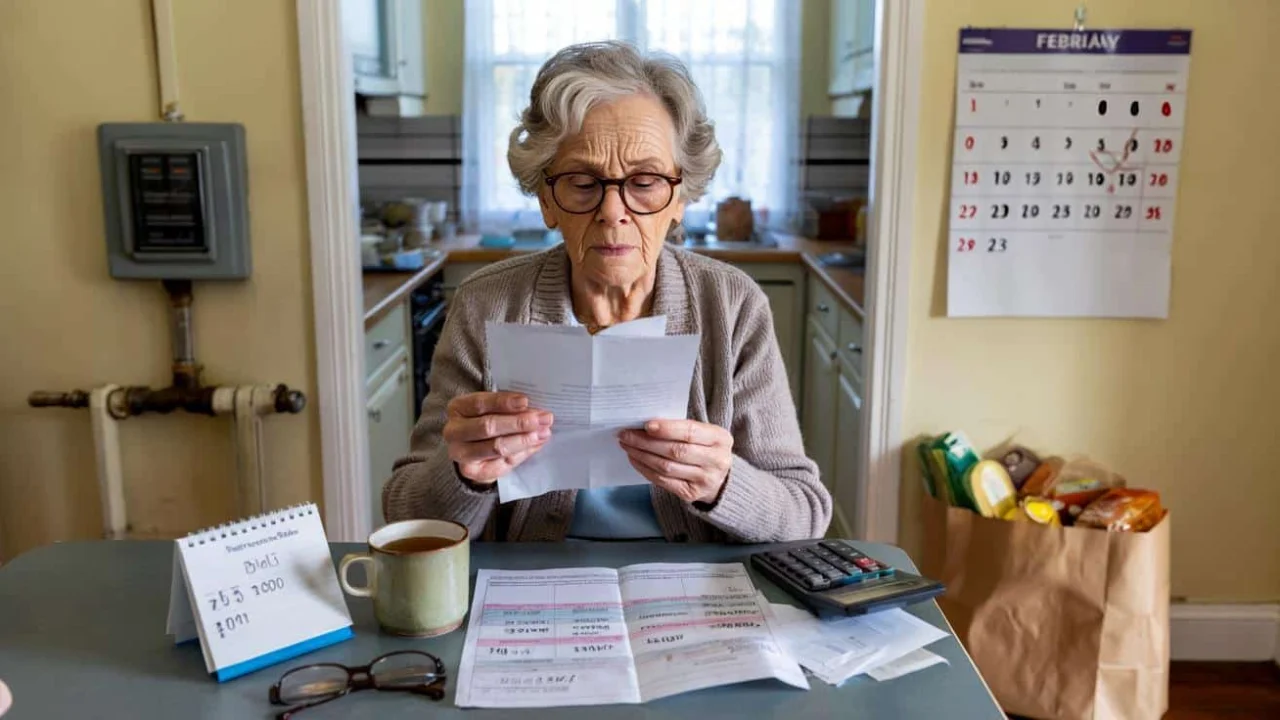

The letter dropped through the door on a grey Tuesday morning, the kind of day when the kettle works harder than the sun. Margaret, 72, thought it was another leaflet about boiler scams or local elections. Instead, it was a thin white envelope with a thick message: her state pension was going down by £140 a month from February.

She read the line three times, as if the numbers might blink and rearrange themselves into something less brutal. The heating clicked off in the background, on its strict timer. She reached for her glasses with the familiar mix of dread and denial so many pensioners now know by heart.

That’s when the real shock hit her.

When the safety net starts to fray

For years, the state pension has been the last solid pillar for millions of older Britons. Not generous. Not luxurious. Just something stable in a world of bus fare hikes, food price surges and rent increases that seem to climb faster than anyone’s income.

So when news spread that a state pension cut had now been officially approved – shaving £140 a month from payments starting in February – it didn’t feel like a policy tweak. It felt like a rug pull.

People talk about “budget adjustments” and “fiscal responsibility.” What it really means is a weekly shop that suddenly doesn’t fit in the basket anymore. It means choosing between heating and eating becomes less of a cliché and more of a daily reality.

“This isn’t just numbers on a spreadsheet,” says David Richardson, a welfare rights adviser who’s been fielding panicked calls since the announcement. “We’re talking about people who’ve worked their entire lives, paid their taxes, and now find themselves having to make impossible choices.”

The state pension cut affects roughly 12 million people across the UK. That’s not a small corner of society – that’s grandparents, neighbours, the people who queue quietly at the post office every week and never complain about waiting.

Breaking down what this actually means

The numbers tell a stark story when you strip away the political language and look at what pensioners are actually facing:

| Current full state pension | £203.85 per week |

| New rate from February | £171.60 per week |

| Monthly reduction | £140 |

| Annual loss | £1,680 |

For someone already living on a tight budget, that £140 monthly cut translates to real decisions:

- Two fewer weeks of groceries each month

- Turning off heating for an extra four hours daily

- Skipping prescription medications to save money

- Cancelling the landline or cutting back on transport

- Choosing between new clothes and household repairs

“The government says they need to balance the books,” explains Sarah Mitchell, a financial adviser specialising in retirement planning. “But they’re balancing them on the backs of people who have the least room to absorb these cuts.”

The timing makes it particularly brutal. February is already one of the most expensive months for older people – heating bills peak, winter clothes need replacing, and many face higher insurance premiums at renewal time.

What makes this state pension cut different from previous adjustments is its scope and speed. There’s no gradual phase-in, no exemptions for the most vulnerable, and no clear timeline for when normal payments might resume.

The ripple effect nobody talks about

When you cut someone’s income by £140 a month, the impact doesn’t stay contained to their household budget. It spreads outward like cracks in ice.

Local shops lose customers who can no longer afford to buy locally. Adult children find themselves stepping in to help parents with bills they shouldn’t need help with. Care homes see residents struggling to pay fees, and some families face impossible decisions about long-term care.

“I’m 74 and I’m looking for work again,” says one pensioner from Yorkshire who asked not to be named. “I haven’t worked in nine years, but £140 a month is the difference between managing and not managing.”

The knock-on effects reach into areas most people don’t consider:

- Increased pressure on food banks and charitable organisations

- More pensioners delaying medical treatment due to cost concerns

- Rising numbers applying for pension credit and housing benefit

- Adult children reducing their own savings to support parents

- Local businesses losing regular customers who can no longer afford their services

Mental health services are already reporting an uptick in anxiety and depression among older adults who received the letters about the state pension cut. The uncertainty hits as hard as the financial impact.

“People who’ve been independent their whole lives are suddenly facing the prospect of asking for help,” notes Dr. Emma Walsh, who works with elderly patients. “That’s not just about money – it’s about dignity and self-worth.”

The cut also affects spending patterns in ways that might surprise policymakers. Pensioners tend to spend locally and immediately – they don’t save tax cuts or investment gains for later. When their income drops, local economies feel it quickly.

Small businesses that rely on steady, local custom – corner shops, local cafes, independent pharmacies – are bracing for a noticeable drop in footfall. These aren’t abstract economic theories; they’re the places where real people work and serve their communities.

Some analysts worry the state pension cut could trigger what economists call a “poverty spiral” – where reduced spending power leads to business closures, which leads to fewer local services, which makes life more expensive for everyone, especially those who can least afford it.

What happens next

The reality is that this state pension cut is happening, starting this February. There’s no appeals process, no opt-out, and no clear indication of when or if payments might return to previous levels.

For millions of pensioners, that means adapting to a new financial reality they didn’t choose and couldn’t prepare for. Some will manage by making difficult cuts to their lifestyle. Others will need help from family, charities, or other government support systems that are already stretched thin.

The government has suggested that other support mechanisms might be enhanced to help offset the impact, but details remain vague. Meanwhile, pensioners are making immediate decisions about how to survive on less money each month.

“The letters have been sent, the decision is made,” says Richardson, the welfare rights adviser. “Now it’s about helping people understand what support is still available and how to access it before they really need it.”

For Margaret, the 72-year-old who opened that grey morning’s letter, the adjustment is already underway. She’s cancelled her newspaper delivery, switched to the cheapest mobile phone plan she could find, and started shopping at discount stores she’d never considered before.

It’s not the retirement she planned, but it’s the one she’s living now.

FAQs

When exactly will the state pension cut start?

The £140 monthly reduction begins with February 2026 payments, affecting all eligible pensioners immediately.

Is there any way to avoid the cut?

No, this is a universal reduction that applies to all state pension recipients with no exemptions or opt-out options.

Will other benefits be increased to compensate?

The government has mentioned possible adjustments to other support systems, but no concrete increases have been confirmed or scheduled.

How long will the cuts last?

There’s currently no official timeline for when payments might return to previous levels or if they will at all.

Can pensioners appeal the decision?

This is a policy change rather than an individual decision, so there’s no appeals process available to individual pensioners.

What support is available for those struggling with the cuts?

Pension credit, housing benefit, and council tax support may still be available, and local councils often have emergency hardship funds for those in severe difficulty.